No matter your field of expertise, every day you’re presented with seemingly impossible challenges. Issues that you or your company can’t seem to crack, even after weeks, months, or years of trying.

How do you approach these impossible challenges? Do you have a strategy that you follow, or do you just hold a brainstorming session and hope for the best? Do you tell yourself, “Think harder!” and pray inspiration will strike?

There’s a better way to solve problems like these — improve the quality of your thinking. Better thinking, problem-solving, and reasoning are skills. They can be developed through self-examination, learning new frameworks, and expanding our mental models.

To solve impossible problems, improve the quality of your thinking.

Lucky for us, brilliant thinkers, creators, entrepreneurs, and philosophers have left behind documentation, frameworks, and tools for considering impossible problems.

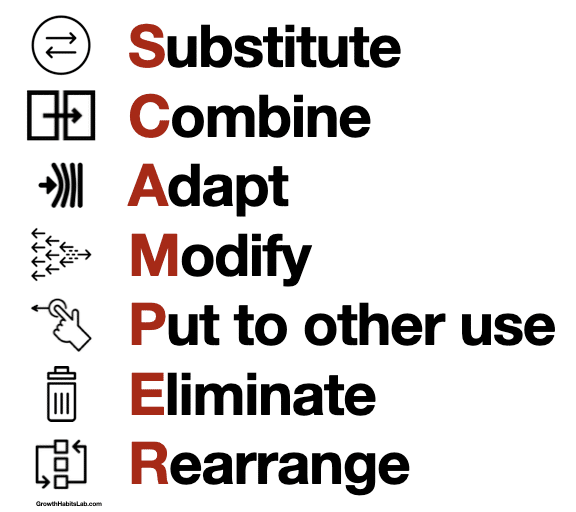

The S.C.A.M.P.E.R. framework is one of those tools.

What is S.C.A.M.P.E.R.?

S.C.A.M.P.E.R. (or SCAMPER) is a framework that helps us manipulate existing ideas and solutions to create new ones. It was created by advertising executive Alex Faickney Osborn in the 1950s and expanded on by educator Bob Eberle.

The underlying premise of S.C.A.M.P.E.R. is the idea of combinational creativity — that is, we can solve problems by transforming existing ideas instead of starting from scratch every time. As Michael Michalko, author of Thinkertoys, put it:

“Manipulation is the brother of creativity.”

S.C.A.M.P.E.R. is a framework that helps us work through the many ways we can reshape an existing idea or product. It stands for:

1. Substitute

To substitute, remove a person, element, or concept and replace it with something else. It’s a trial-and-error process that takes time but can produce incredible results.

Examples of “Substitute” in action

1. The Java Log

Rod Sprules, a Canadian engineer, invented a clean-burning fireplace log made of 65% recycled coffee grounds. According to Sprules, the logs burned brighter and hotter than traditional sawdust logs and produce 88% less carbon monoxide than wood. It took the inventor lots of trial and error before he found the right combination of materials for the popular Java Log.

2. Edison’s Lightbulb

It took inventor Thomas Edison and his team two years of trial-and-error substitution to create the filament lightbulb. They had at least three thousand different theories before they discovered one that worked. He later described the process of substitution like this:

“I have not failed 10,000 times. I have not failed once. I have succeeded in proving that those 10,000 ways will not work. When I have eliminated the ways that will not work, I will find the way that will work.”

To “Substitute,” start by asking yourself:

- What are the parts of this challenge? How can we switch them out for something new? (First Principles Thinking can help you break down your problem into its simpliest parts)

- Can we replace an ingredient, material, or power source in this product for another?

- What would happen if we changed the location of this challenge?

2. Combine

“…All ideas are second-hand — consciously and unconsciously drawn from a million outside sources, and daily use by the garnerer with a pride and satisfaction born of the superstition that he originated them.”

- Mark Twain

Can you combine elements from different solutions to come up with something completely new? By “combining,” you can think about your problem in new ways and break out of the usual thinking.

Examples of “Combine” in Action

1. The iPhone

When Apple engineers created the iPhone, they presented a radically new product whose parts were pretty familiar to most people. The iPhone was just an iPod, combined with a mobile phone and an internet browser.

Apple itself even referred to the iPhone as a combination of existing ideas in the product’s original press release:

“Apple® today introduced iPhone, combining three products — a revolutionary mobile phone, a widescreen iPod® with touch controls, and a breakthrough Internet communications device… — into one small and lightweight handheld device.”

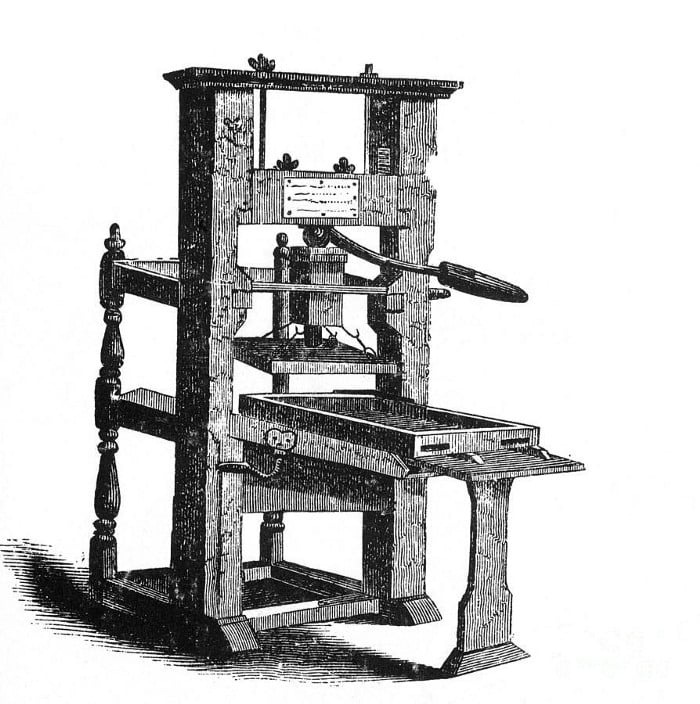

2. The Printing Press

In the 1400s, craftsman Johannes Gutenberg combined the mechanics of a coin punch with a wine press to create the first printing press. This use of combinational creativity allowed Gutenberg to invent a machine that changed the world.

To “Combine,” start by asking yourself:

- Do we have a solution that could merge with another to create something unique?

- What other products or solutions solve a part of this issue, but not all of it? Could we combine those products to solve the whole challenge?

- Could we package existing products or solutions together to create a new and better product?

3. Adapt

“There’s nothing new under the sun.”

This approach means looking to other fields, products, or solutions for inspiration. For example, scientists take inspiration from nature to find features that we can apply to a technological problem.

Examples of “Adapt” in action

1. Bacteria-fighting Shark Skin

The design of sharkskin scales, which allows algae to slide easily off of sharks’ skin, has been adapted to help reduce bacteria on products from yoga mats to catheter tubes.

2. Ballpoint Pens for your Armpits

Chemist Helen Barnett Diserens invented the roll-on deodorant delivery system in the 1940s. She was inspired by a suggestion from a colleague to adapt ballpoint pen technology for armpits.

3. Advanced Wind Turbines

Inspired by the bumps on a humpback whale’s flippers, Professor Frank Fish invented a new type of wind turbine. After years of studying whale flippers, he made a discovery. As the Guardian put it:

“The bumps cause water to flow over the flippers more smoothly, giving the giant mammal the ability to swim tight circles around its prey.”

By adapting these bumps for wind turbines, Professor Fish created a turbine that only needed half the number of blades to generate the same amount of power.

To “Adapt,” start by asking yourself:

- Is there something that’s working well for another challenge that might fix your current problem?

- Are there any examples from nature that might more effectively solve your problem?

- Has anyone outside your field solved this problem already? Can you adapt or be inspired by their invention?

4. Modify (Maximize or Minimize)

Modifying your challenge means growing, or shrinking parts of your challenge can give you a fresh perspective on ways to solve it. You can also consider changing the audience of an existing product to expand its use.

Examples of “Modify” in Action

1. The Accidental Slinky

The Slinky was invented when Naval engineer Richard Jones created a toy from an experiment. Initially, he was trying to develop a tool to monitor power on naval battleships. He accidentally dropped one of the springs on the ground, and it started bouncing around. Instead of writing this off as a mistake, Jones recognized the opportunity, and the Slinky was born.

To apply “Modify,” start by asking yourself:

- Can you increase the size of your business or production so “economies of scale” start to work in your favor?

- Are there parts of your product or service that you could eliminate? Would this make it easier for people to use your product?

- Are there parts of your product or service that might benefit from playing a more significant role? Are there materials you use in one component that might improve your overall product if you used more of it?

5. Put to other use

In this step, we consider how putting a solution to another use might help us solve our problem. This is closely related to Modify, in that one of the ways we can modify a solution is to put it to other use (like the Slinky example).

Examples of “Put to other use” in action

1. Diamonds: From Industry to Romance

The De Beers mining company took diamonds — which until the early 1900s were mainly used in industrial settings — and “put them to other use” when they popularized the diamond engagement ring. In just 40 years, their wholesale diamond sales in the U.S. increased from $23 million to $2.1 billion, an increase of more than 9000%.

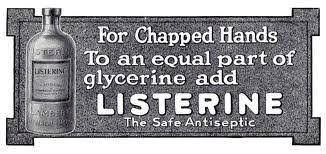

2. Listerine: From Floor Cleaner to Mouthwash

This might make you a little nauseous, but your morning mouthwash was originally marketed as a floor cleaner and general purpose antiseptic. Listerine wasn’t successful until it was rebranded as a cure for bad breath, with sales rising more than 6800%.

To apply “Put to other use,” start by asking yourself:

- Can an existing product be adapted to other uses, customer groups, or rebranded to solve a different need?

- Is there an existing product, service, or solution that might solve our problem, even if it’s not the intended use?

6. Eliminate

Eliminate is an often-overlooked, but genius, problem-solving strategy. Our brains are actually hardwired to jump straight into doing more things, or adding new things, rather than taking a moment to ask if “eliminating” might be a better strategy.

Why? It’s down to something called Action Bias. It describes the human tendency to jump straight to doing something, even if it leads to a worse outcome than doing nothing. For example, let’s say your business’s profit is declining. A manager that’s fallen victim to Action Bias might immediately declare that the company should launch a new product — without deciding if a new product would solve the profit problem.

In fact, research has found that people “systematically overlook” elimination as a strategy, in favor of ideas that add things. Benjamin Converse, a social psychologist described it this way:

“Additive solutions have sort of a privileged status — they tend to come to mind quickly and easily. Subtractive solutions… take more effort to find.”

An example of “Eliminate” in action

1. Pedal-less Bikes for Kids

For many years children learned to ride their bikes with training wheels. But after an inventor questioned the benefits of training wheels, the pedal-less two-wheel bike was born. It helps kids work on the physical coordination needed to ride a bike faster than training wheels or tricycles.

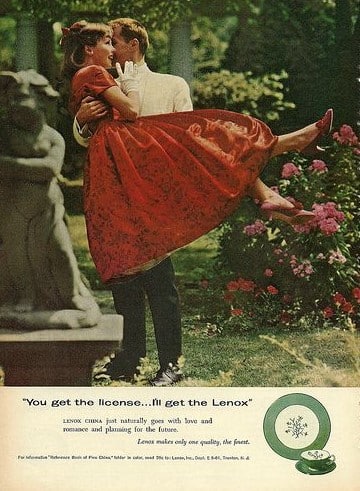

2. Lenox China: From Dining Sets to Bridal Gifts

In the 1950s, Lenox China was a premium china maker that designed place settings for the rich and famous (even the White House had a set of Lenox China).

But to offer their premium place settings to the American public, Lenox knew it would need to divide a major purchase — a set of china — into smaller, cheaper subsets. So they eliminated their full dining set in favor of individually packaged place settings, buffet settings, and tableware.

Lenox also became the first company to develop a bridal registry for its customers to market these new products. The registry’s intent is to help guests buy gifts for the couple. Registries meant that the high cost of a dining set could be broken down and distributed among lots of guests, now that Lenox dining sets were available to buy in smaller subsets.

The advertising firm D’Arcy then developed a famous ad campaign for engaged couples, with the tagline “You get the license… I’ll get the Lenox.”

To apply “Eliminate,” start by asking yourself:

- What would happen if you broke down parts of your product or experience? Could it appeal to a broader range of customers if it were cheaper, easier to buy, or had fewer options?

- Would you resolve any issues by simply removing parts of your product, or eliminating your current customers in favor of a different target group?

7. Rearrange

“Ideas rose in crowds; I felt them collide until pairs interlocked, so to speak, making a stable combination.”

- Henri Poincaré, Mathematician

When you rearrange the sequence, components, timing, or pace of an experience, you might find that this new approach solves many of your issues. Try rethinking the order in which customers interact with your product or service. The results might surprise you.

Examples of “Rearrange” in Action

1. Differentiating the “Golden Arches”

According to Thinkertoys, Ray Kroc wanted to make McDonald’s feel different than any other fast-food restaurant. His solution was to rearrange the original red and white prototype store into what’s now known as the “Golden Arches.” Kroc also added one of the first drive-thru lanes to his stores, flipping the restaurant experience on its head and allowing customers to take McDonald’s home or eat on the road.

To apply “Rearrange,” start by asking yourself:

- Would reordering our customer journey differentiate us from other brands?

- Could we create a more fun or effective experience if we reordered the component parts?

- Could we flip, reverse, or otherwise rearrange how customers interact with our product? What would happen if we put the last part first?

The Bottom Line

The S.C.A.M.P.E.R. model is an excellent example of combinational creativity at work — a solution doesn’t have to be completely new to be innovative and effective.

Although the idea of combinational creativity might not be as sexy as a eureka moment, it’s incredibly effective.

Professor Amar Bhide studied the origins of successful start-ups and found that 70% were based on ideas adapted from their previous experience. Basically, they took an existing idea and made it better.

Try out the S.C.A.M.P.E.R. framework on your most formidable challenge and see how it works for you. And bear in mind the words of one of the most famous combinational creatives, Steve Jobs:

“Creativity is just connecting things.”